Improving Livestock Drinking Water Quality Using a Low-Cost, Locally Available Coagulant in the Global South

By Harinder P.S. Makkar1

1International Consultant, Sustainable Bioeconomy, Vienna, Austria (Formerly at FAO/IAEA, University of Hohenheim)

An overview of an array of uses of moringa tree parts was presented in Broadening Horizons No. 60. Here, the applications of moringa seeds, with a focus on water purification are presented.

Drinking water is essential for maintaining livestock health and optimizing production, as it plays a critical role in digestion, nutrient absorption, temperature regulation, and overall metabolic processes. Adequate and clean water intake supports efficient feed utilization, proper rumen function in ruminants, and helps prevent dehydration, heat stress, and metabolic disorders, thereby improving growth rates, milk yield, reproductive performance, and immune function. In contrast, poor-quality water contaminated with excessive salts, pathogens, organic matter, or toxic substances can reduce water intake, depress feed consumption, and lead to digestive disturbances, poisoning, or disease outbreaks. Prolonged consumption of contaminated or unpalatable water can result in reduced productivity, increased morbidity, and compromised animal welfare, highlighting the importance of providing livestock with a consistent supply of clean, safe drinking water.

Moringa Coagulants

Coagulant compounds can be isolated from Moringa seeds either before or after oil extraction. The extracted oil has valuable applications in heavy machinery, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries, while the remaining seed cake serves as a source of natural coagulants for water treatment.

Coagulants for Water Purification

Coagulation–flocculation, followed by sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection, is widely used in the global water treatment industry. Providing potable water remains a major challenge, particularly in developing countries, due to the high cost and import dependence of conventional treatment chemicals. These typically include alum for coagulation, polyelectrolytes as coagulant aids, lime for softening and pH adjustment, and chlorine for disinfection, all of which require scarce foreign exchange. Coagulants used for turbidity removal are generally classified as natural, inorganic, or synthetic organic polymers. Inorganic coagulants, especially aluminum salts, are the most widely used; however, their use has raised significant concerns. Residual aluminum in treated water has been associated with health risks, including neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (Martyn et al., 1989). Ferric salts and synthetic polymers have also been applied, but with limited success (Letterman and Pero, 1990). Moreover, prolonged use of chemicals such as aluminum sulfate, chlorine, potassium permanganate, ferric sulfate, lime, polyphosphates, and fluorides may contribute to adverse health effects. Some synthetic organic polymers, particularly those containing acrylamide monomers, are of additional concern due to their neurotoxic and carcinogenic properties.

Moringa Coagulants: A Natural Alternative

Given these limitations, there is a strong need to develop cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and safer alternatives to conventional coagulants. Naturally occurring coagulants are biodegradable and generally considered safe for human health. Extracts from Moringa seeds have been shown to significantly reduce turbidity and bacterial loads in raw water (Muyibi and Evison, 1995). Studies have further demonstrated that crushed M. oleifera seeds can be as effective as aluminum salts in coagulating raw water (Nzeyimana and Mary, 2024; Hassan et al., 2025; Akinbolawa et al., 2025). Moringa oleifera is a small, fast-growing, drought-tolerant deciduous tree, making it a sustainable and locally available resource for water treatment, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Nature of Moringa Coagulants and Mechanism of Coagulation

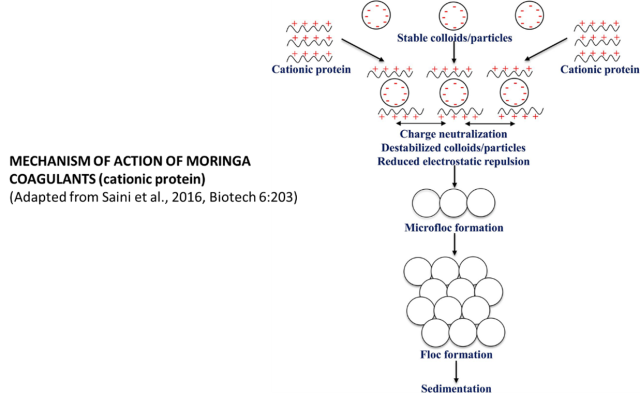

The active components responsible for the coagulation activity of aqueous Moringa oleifera seed extracts are primarily dimeric cationic proteins (Figure 1). Early studies indicate that these active substances consist of water-soluble cationic peptides with molecular weights ranging from 6 to 16 kDa and isoelectric points around pH 10 (Gassenschmidt et al., 1991; Ndabigengesere et al., 1995). One such peptide, designated MO2.1, was purified to homogeneity and sequenced, and it demonstrated strong flocculating activity in glass powder suspensions (Gassenschmidt et al., 1995). The flocculation behavior was attributed to a patch charge mechanism, arising from the peptide’s low molecular weight and high positive charge density.

Figure 1. Nature of Moringa coagulants and mechanism of their action

In addition to proteinaceous components, a non-protein active fraction with a molecular mass of approximately 3 kDa has been isolated from M. oleifera seeds and shown to effectively flocculate kaolin suspensions (Okuda et al., 2001). The proposed mechanism in this case involves physical enmeshment of suspended particles by insoluble, net-like structures formed during coagulation.

Overall, the coagulation mechanism of Moringa seed coagulants is believed to involve a combination of adsorption and charge neutralization, as well as interparticle bridging (Figure 1). Variations in coagulation efficiency reported among seeds from different sources are likely due to differences in protein content, seed maturity, and growing conditions, which influence the nature and concentration of the active coagulating agents.

Water purification using moringa seeds

Treatment of water with Moringa oleifera seed extracts can result in a 1–4 log-unit reduction of pathogens, including faecal bacteria and Schistosoma mansoni cercariae. A surface water study conducted in Ghana for domestic use reported a 91% reduction in faecal coliform levels following treatment with M. oleifera. In the same study, more than 90% reduction of Schistosoma mansoni was achieved, demonstrating the potential of Moringa seed treatment as an effective alternative for reducing the risk of schistosomiasis transmission (Pandit and Kumar, 2015).

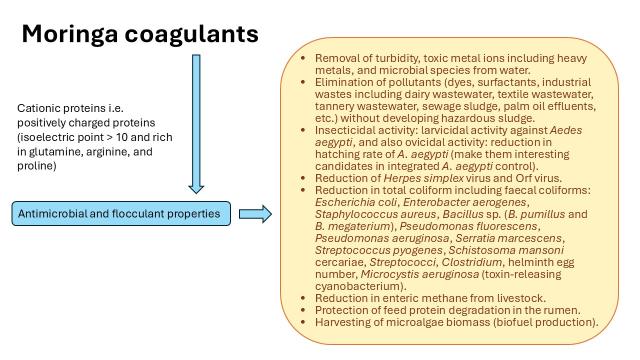

Beyond coagulation, Moringa seed proteins exhibit broad antimicrobial activity against a range of pathogens, including parasites (Kansal and Kumar, 2014). Agra-Neto et al. (2014) and de Lima Santos et al. (2014) further demonstrated that Moringa seed proteins possess strong larvicidal activity against fourth-instar Aedes aegypti larvae that are susceptible to organophosphates. Additionally, Moringa proteins have been shown to significantly reduce Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in water (Petersen et al., 2016), and to remove Microcystis aeruginosa and microcystins from municipal treated water (Alhaithlout et al., 2024). Other studies have reported that M. oleifera seed treatment can reduce helminth egg concentrations by 94–99.5% and decrease turbidity by up to 85.96% across different types of irrigation water (Figure 2), highlighting its effectiveness as a low-cost, multifunctional water treatment option.

Figure 2. Uses of Moringa coagulants

A single Moringa oleifera tree can produce approximately 2,000 seeds per year, which is sufficient to treat about 6,000 L of water when applied at a dosage of 50 mg/L. Studies have shown that the optimum M. oleifera dosage for treating water with turbidity levels between 40 and 200 Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) ranges from 30 to 55 mg/L. The coagulation process is generally not significantly affected by pH fluctuations; however, optimal performance has been observed at around pH 6.5 and at higher temperatures. Seed-age also influences effectiveness, with seeds older than two years showing reduced coagulation efficiency.

Both shelled and unshelled dry M. oleifera seeds can be used as coagulants, although shelled seeds have been reported to be more effective. One limitation of using crude Moringa seed extracts is the potential increase in organic matter concentration in treated water. This added organic load can increase chlorine demand and act as a precursor for trihalomethane formation during chlorination. Therefore, the use of M. oleifera seeds as coagulants in water and wastewater treatment is recommended only after adequate purification of the active protein fractions. In practice, Moringa seeds have also been combined with Sudanese bentonite clays for treating Nile water in Sudanese villages. Overall, reviewed studies indicate that crude Moringa spp. extracts can achieve turbidity reductions comparable to those obtained with aluminum sulfate, while simultaneously reducing the load of undesirable microorganisms.

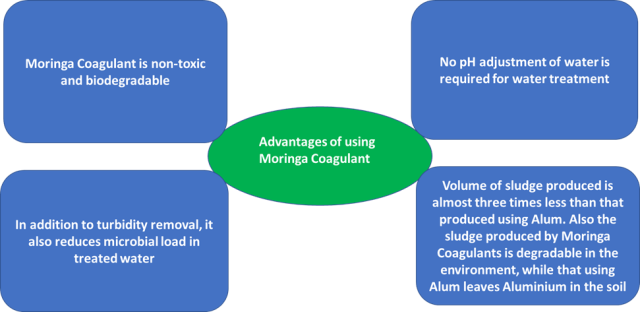

Advantage of moringa coagulants over alum

Despite exhibiting treatment performance comparable to alum, Moringa oleifera seed extracts offer several important advantages (Figure 3). Non-purified aqueous Moringa extracts are effective across a wide pH range and, unlike alum, do not significantly alter the final pH of treated water. In addition, the volume of sludge generated using M. oleifera extracts can be up to five times lower than that produced by aluminum sulfate. This difference is partly attributed to the chemically bound water associated with aluminum in commercial alum, where waters of hydration increase sludge volume and reduce the amount of recoverable treated water—an important consideration in water-scarce regions.

Although sludges from both treatments contain inorganic components and are biodegradable to some extent, this factor is of limited relevance for domestic water treatment. However, Moringa-derived sludge may offer potential advantages for land application due to its possible nutritional value. In contrast, land application of alum sludge is often undesirable because it can immobilize inorganic phosphorus in soils, reducing plant availability, and may also pose risks of aluminum phytotoxicity depending on pH-dependent solubility. Overall, these factors highlight several environmental, operational, and sustainability advantages of Moringa coagulants over conventional synthetic coagulants (Sulaiman et al., 2017).

Figure 3. Advantages of Moringa coagulants

Amante et al. (2015) conducted a life cycle assessment (LCA) comparing coagulants derived from Moringa oleifera seeds with conventional chemical coagulants. Their findings showed that the energy consumption required to produce one kilogram of aluminum sulfate (Al₂(SO₄)₃) is nearly 40% higher than that required for M. oleifera–based coagulants. In addition, carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions associated with alum production were approximately 80% greater than those linked to Moringa-based alternatives. Beyond effective turbidity removal, coagulants derived from residual Moringa oil cake offer the advantages of lower energy demand, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and no significant alteration of water pH or conductivity.

Towards Optimal Extraction and Use

Numerous studies have explored methods for extracting coagulants from Moringa seeds, kernels, and seed cake using different solvents, blending techniques, and filtration systems. These approaches have been developed both for direct use of crude extracts and for purification of the active compounds for specialized applications. The potential for large-scale isolation of Moringa coagulants for drinking water purification—applicable to both animals and humans—has been clearly identified and could be further developed. In addition to water treatment, purified Moringa coagulants also show promise for applications in the cosmetic industry.

Water quality is as important as water quantity, as contaminated sources expose animals to pathogens, toxins, and nutrient imbalances that negatively affect health and productivity. Countries in the Global South, in particular, could benefit from exploiting Moringa seed coagulants initially in less-purified forms for livestock drinking water. With accumulated experience, their application could later be extended to human drinking water. For livestock systems, appropriate delivery mechanisms—such as the use of kernels or seed meal—would need to be developed. While implementation may be relatively straightforward for housed animals, it presents challenges for grazing animals reliant on ponds or surface water. In such cases, water bodies could be partitioned into treatment and drinking sections connected by simple one-way flow valves or similar low-cost systems. Alternative practical solutions may also be explored.

In more purified forms, Moringa-derived coagulants could be utilized in high-value products such as anti-aging creams and facial masks, for which there is a substantial market in industrialized regions, further enhancing the economic and sustainability potential of this natural resource.

Conclusion

Ensuring access to safe and clean drinking water is critical for livestock health, productivity, and welfare, particularly in the resource-limited settings of the Global South. Moringa oleifera seeds offer a promising, low-cost, and locally available alternative to conventional chemical coagulants for water purification. Their active components, primarily cationic proteins and peptides, effectively reduce turbidity, remove pathogens, and exhibit antimicrobial and larvicidal activities against a range of microorganisms and parasites. Compared with conventional coagulants such as aluminum sulfate, Moringa seed extracts produce significantly lower sludge volumes, do not alter water pH, and reduce environmental impacts, including energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. Practical applications for livestock drinking water can be achieved using crude seed extracts, while more purified forms have potential for human water treatment and high-value industrial uses, such as cosmetics. With appropriate extraction, dosing, and delivery systems, Moringa-based coagulants represent a sustainable, multifunctional solution for improving water quality, reducing disease risk, and supporting livestock production, while also offering socio-economic and environmental benefits.

References

- Agra-Neto, A. C.; Thiago Henrique Napoleão; Emmanuel Viana Pontual; Nataly Diniz de Lima Santos; Luciana de Andrade Luz; Cláudia Maria Fontes de Oliveira; Maria Alice Varjal de Melo-Santos; Luana Cassandra Breitenbach Barroso Coelho; Daniela Maria do Amaral Ferraz Navarro; Patrícia Maria Guedes Paiva, 2014. Effect of Moringa oleifera lectins on survival and enzyme activities of Aedes aegypti larvae susceptible and resistant to organophosphate. Parasitol Res 113, 175–184.

- Akinbolawa Olujimi A.; Oloruntoba, Elizabeth O.; Olu Owolabi Bamidele I.; Micheal Abimbola Oladosu; Moses Adondua Abah, 2025. Evaluation of Plant-Based and Commercially Available Flocculant-Disinfectants for Water Purification. Annal of Pub Health & Epidemiol. 2(5): 2025. APHE.MS.ID.000550. DOI: 10.33552/APHE.2025.03.000550

- Alhaithloul HAS; Mohamed ZA; Saber AA; Alsudays IM; Abdein MA; Alqahtani MM; AbuSetta NG; Elkelish A; Pérez LM; Albalwe FM; Bakr AA, 2024. Performance evaluation of Moringa oleifera seeds aqueous extract for removing Microcystis aeruginosa and microcystins from municipal treated-water. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024 Feb 1;11:1329431. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1329431.

- Amante, B.; Lopez-Grimau, V.; Smith, T., 2015. Valuation of oil extraction residue from Moringa oleifera seeds for water purification in Burkina Faso. Desalination and Water Treatment 57, 2743-2749.

- de Lima Santos, N.D.; Paixo, K.D.S.; Napoleao, T.H.; Trindade, P.B.; Pinto, M.R.; Breitenbach Barroso Coelho, L.C.; Eiras, A.E.; do Amaral Ferraz Navarro, D.M.; Guedes Paiva, P.M., 2014. Evaluation of Moringa oleifera seed lectin in traps for the capture of Aedes aegypti eggs and adults under semi-field conditions. Parasitology Research 113, 1837-1842.

- Gassenschmidt U; Jany K.D.; Tauscher B.; Niebergall H., 1995. Isolation and characterization of a flocculating protein from Moringa oleifera Lam. Biochim Biophys Acta 1243(3), 477-81.

- Hassan A. B.; Hasan M. B.; Shadhar M. H.; Al-Kanany N. B. H., 2025. Natural coagulant efficiency of Moringa oleifera seeds in raw water treatment. Journal of Engineering Sciences (Ukraine), Vol. 12(2), pp. H1–H9. https://doi.org/10.21272/jes.2025.12(2).h1.

- Kansal, S.K.; Kumari, A., 2014. Potential of M. oleifera for the Treatment of Water and Wastewater. Chemical Reviews 114, 4993-5010.

- Letterman, R.D.; Pero R.W., 1990. Contaminants in polyelectrolytes used in water treatment. Am Water Works Assoc J 82:87–97.

- Martyn, C.N.; Barker, D.J.P.; Osmond, C.; Harris, E.C.; Edwardson, J.A.; Lacey, R.F., 1989. Geographical relation between Alzheimer’s desease and aluminium in drinking water. The Lancet 1:59–62.

- Muyibi, S.A.; Evison, L.M., 1995. Optimizing physical parameters affecting coagulation of turbid water with Moringa oleifera seeds. Water Res 29, 2689–2695.

- Ndabigengesere A; Narasiah KS; Talbot BG, 1995. Active agents and mechanism of coagulation of turbid waters using Moringa oleifera. Water Res 29, 703–710

- Nzeyimana, B.S.; Mary, A.D.C., 2024. Sustainable sewage water treatment based on natural plant coagulant: Moringa oleifera. Discov Water 4, 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43832-024-00069-x

- Okuda, T.; Baes, A.U.; Nishijima, W.; Okada, M., 2001. Isolation and characterization of coagulant extracted from Moringa oleifera seed by salt solution. Water Research 35, 405-410.

- Pandit, A.B.; Kumar, J.K., 2015. Clean Water for Developing Countries, In: Prausnitz, J.M. (Ed.), Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Vol 6, pp. 217-246.

- Petersen, H.H.; T.B. Petersen, H.L. Enemark; A. Olsena., 2016. A. Dalsgaarda Removal of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in low quality water using Moringa oleifera seed extract as coagulant. Food and Waterborne Parasitology 3, 1-8.

- Saini, R.K.; Sivanesan, I.; Keum, YS, 2016. Phytochemicals of Moringa oleifera: a review of their nutritional, therapeutic and industrial significance. 3 Biotech 6, 203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0526-3

- Sulaiman, M.; Daniel Andrawus Zhigila; Kabiru Mohammed; Danladi Mohammed Umar; Babale Aliyu; Fazilah Abd Manan, 2017. Moringa oleifera seed as alternative natural coagulant for potential application in water treatment: A review. Journal of Advanced Review on Scientific Research 30(1), 1-11.